When I was six years old, my mother took to her bed. I don’t know how long she stayed there, because time is elastic to a child, but my best guess is several months. My family was living in the tiny western town of McDermitt, which straddles the border between Nevada and Oregon, about halfway from Reno to Boise as the crow flies. The area is high desert, part of a caldera formed sixteen million years ago by the Yellowstone Hotspot, which filled it with valuable ores, especially cinnabar, source of mercury. My father had landed a good job mining that ore at the open-pit McDermitt Mine leaving the family in a small travel trailer near the handful of buildings that passed for the town of McDermitt.

When I say the trailer was small I don’t exaggerate. It had an eight-foot-square seating area, a tiny kitchen, one low bunk, and a bathroom. At night, my parents shared the bunk, while my siblings and I slept two to a wide shelf in the back of the trailer. I liked our cramped sleeping arrangements. With my brother beside me on our shared shelf, I was safer at night than I had ever been–a story for another time. My mother, however, was miserable. Used to living in a spacious house on her parents’ farm, she hated the small, isolated trailer. Though my father made good money at the mine, he worked very long hours, including Sundays, leaving her with four young children and no family support. One by one, she stopped doing necessary tasks until, finally, she stopped getting up in the morning.

One by one, I took over those jobs. Every morning, after my father left at dawn for his long drive to the McDermitt Mine, I roused my siblings from their shelves, dressed them, and poured their cereal and milk. When everyone had finished eating, I washed the dishes before beginning my most important job of the day: helping my mother get well. Though only six, I knew what to do; I had seen my mother do it many times. I lined up my siblings in the order of our ages beside my mother’s low bunk. As she wept, we all knelt with our elbows on the bed and our hands folded.

“Heavenly Father,” I began, “please help Mommy get better.” I explained that she was sick and recalled that she had prayed for us when we were sick, but mainly I pleaded with God to heal my mother while my siblings knelt quietly waiting for their cue.

“In the name of Jesus Christ,” I prompted, and we all said “Amen” in unison, even the youngest, still in diapers. If I conducted the prayers correctly, I thought, God would heal my ailing mother, so I orchestrated what I hoped were the most perfect, heartfelt prayers four children ever aimed heavenward. Unfortunately, our efforts were in vain. The straighter we knelt, the more neatly we folded our hands, the more fervently we prayed, the harder my mother sobbed. In other words, my best efforts weren’t just fruitless; they made her worse.

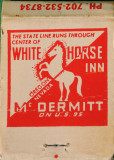

After this daily failure, I took my siblings out of the trailer to give my mother some peace. We played with pop guns and threw rocks in the front yard for a while. Sometimes we found a dead animal and poked it with a stick. Around mid-morning, all holding hands, we crossed the highway to the White Horse Inn, a two-story cube of red-and-white painted cinderblock fronted by a cement porch with a crooked red roof. We climbed onto barstools and drank root beer in the company of men drinking regular beer, most of them Paiute and Shoshone from the Fort McDermitt Reservation. The beer-drinkers liked us, and I suppose we were cute with our white-blonde hair and our little legs dangling from our barstools. We didn’t know that we were supposed to pay for our root beer, but no one ever mentioned money, just gave each of us a frosty bottle, joked with us, and watched out for us.

Just before lunch, my mother arrived, her face pale, her eyes red-rimmed.

“I’ve been looking all over for you kids,” she said wearily–always the same line, which puzzled me because my siblings and I followed exactly the same routine every day and could always be found at the White Horse Inn. When she arrived, we sucked down the remains of our root beers and meekly followed her back to the trailer, where I helped her make peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for lunch.

Mom tried to remain functional for the rest of the day and sometimes succeeded with the help of Sister and Elder Holliday, Mormon missionaries who lived out on the reservation. When the Hollidays came over–or when we went to their house for church–my mother generally remained upright and dry-eyed. Sister and Elder Holliday had the power to make my mother better, so I was always happy to hear the sound of their car and Sister Holliday’s high “Yoo hoo!” outside the trailer. At the same time, I felt bad because they did so easily something I couldn’t do at all. It was strong evidence of what I had suspected for a while: that God didn’t like me enough to answer my prayers, no matter how perfectly I said them.

My father usually arrived home well after dark. It was odd; he normally looms larger in my memory than my mother and my siblings put together, yet he was a low-key presence during the months when my mother cried in bed. Before he walked through the door, my mother roused herself to prepare a simple meal–I remember a lot of buttered noodles–and make sure there was enough milk for dinner and the following day’s breakfast. After dinner, she became almost normal, washing the dishes as we kids played “fish” then reading us Bible stories as we drifted off to sleep. But in the morning, we woke to the sound of her crying, and the cycle began again.

This story raises several issues, but I want to talk about parentification, a breach of the generational boundary between parent and child. When a parent stops parenting, to any degree and for any reason, a child normally tries to fill the gap, no matter how far beyond the child’s capabilities the abandoned parental duties may be. The child who steps up is usually the oldest child or the oldest child of the right gender, depending on the responsibilities involved and the dynamics of the family. Parentification is not wholly negative; a little dose can confer developmental benefits, allowing children to “try on” adult roles and develop competencies that can help them in life. When responsibilities become too onerous, however, or when a parent and a child swap roles, parentification can cause serious problems, some of them life-long.

Psychologists distinguish two types of harmful parentification: instrumental and emotional. The instrumentally parentified child works to meet the material and physical needs of the family, everything from paid employment to caring for children, parents, and grandparents. When I dressed and fed my siblings every morning then shepherded them over to the White Horse Inn for root beer, I was an example of instrumental parentification.

Emotional parentification is a little harder to define, but it essentially means meeting developmentally inappropriate social and emotional needs of a parent–or of other family members on behalf of a parent. Common examples include:

- serving as a parent’s confidante or close friend;

- serving as a parent’s surrogate spouse or romantic partner;

- serving as a parent’s parent;

- mediating conflict between parents and/or siblings;

- providing nurturance and emotional support for siblings;

Because I parented my mother–or tried to–and supported my siblings, I was also an example of emotional parentification. Instrumental and emotional parentification are often entangled this way, though it’s still useful to distinguish them because purely instrumental parentification can be non-pathological, especially in cultures where it is commonplace.

What hurts parentified children is the sacrifice of their own needs in order to meet a parent’s needs, a family’s needs, or an ad-hoc family’s needs. The fourteen-year-olds comforting five-year-olds in US detention camps need comfort themselves but put their own needs aside, which may have consequences far beyond the camps. They may learn to devalue their own feelings or not to feel them at all. At every stage of childhood, human beings have emotional needs that must be met and developmental tasks that must be performed. When these needs and tasks are neglected, children suffer psychological and social injuries that may be hard to overcome.

For example, as they mature, children must develop social networks outside the home and begin to get some of their emotional needs met there. Older children and adolescents should learn to navigate social situations and explore emerging sexual and romantic feelings with peers, not with family members. Parents can disrupt this learning in many ways, but one of the most common is to siphon off the social energy that would normally flow out into the world. A twelve-year-old girl who supports her mother through a divorce and re-entry into the dating world, including lengthy, intimate discussions of every romantic development, may feel proud and pleased when mom describes her as “my best friend” or “my therapist.” But if being mom’s confidante is taking the place of finding confidantes her own age, the girl may not learn to interact with peers at this crucial stage and may struggle the rest of her life to make friends.

My own parentification, though severe, did not go on long enough to have lasting developmental consequences. One day, my mother packed her suitcases, scooped up my siblings, and left, announcing that her mother was sick and needed her. An aunt later told me that my father had sent her away to collect herself, which she did, returning as the bustling Mormon homemaker I would know for most of my childhood. I remained parentified while she was gone, however, as my father expected me to clean the trailer and have dinner on the table when he came home from the mine.

My experience did have effects, however, some short-term and some long-term, all typical of parentification. First, for the rest of my childhood, I felt responsible for my siblings. When one of them had a problem with a teacher, I read that teacher the riot act, even when I was half the teacher’s size. I picked on my siblings, like all abused children, but I also protected them fiercely and never lost the sense that I was personally responsible for their well-being.

I also got angry, really angry. Explosive anger is common in parentified children, and I had my full share, which I expressed in classic fashion: arson. My siblings remember my fire as “that time you burned down the town,” which is less dramatic than it sounds, given that the town of McDermitt consisted of a few buildings clustered at the edge of an Indian reservation. But I did not burn down the town–or even try to burn down the town–because that would have meant destroying the White Horse Inn, which I loved.

Instead, I took a pack of matches from the White Horse Inn to a stack of hay bales in a field. I lit a match and touched it to a bale I could reach, which caught fire. I watched the fire for a while then went home to get my brother, who would appreciate the spectacle. By the time we returned, the fire had spread to a barn filled with hay bales. A few people tried to extinguish the fire with hoses while others carried or drove equipment out of the barn. My brother remembers people being carried out of the barn, but he was only four and could have imagined it. I don’t remember seeing anything like that. I do remember the sheriff coming by later to ask me whether I had set the fire, which I admitted. He told me not to do it again, and that was the end of my arson career.

One more effect of my parentification at six emerged almost forty-five years later–and required some hard work to excavate. The occasion was a stay at my parents’ home to nurse my mother after a heart attack followed by emergency surgery. According to her doctors, she was healing well and headed for a full recovery. According to her doctors, her pain was minimal, yet she spent all day and all night in anguished weeping and could not be comforted. I tried everything: preparing tempting snacks, rubbing her feet, listening to her wail, distracting her with gossip. Nothing worked, even the ever-more-powerful painkillers she was prescribed. I felt utterly helpless, and, before long, fell into the worst depression I had experienced since getting sober twenty years earlier, a depression that didn’t lift when I returned home.

A wise friend helped me make the connection to the little girl in the trailer who had tried and failed to make her mother feel better. (I describe this conversation at length in my book Iron Legacy.) At six, I had assumed responsibility for my mother’s happiness, a soul-crushing burden that many parentified children carry for a lifetime. Decades later, when I found myself in a situation similar to the one in the trailer, I picked that burden up again without realizing it. After I took a Survivor’s Workshop to deal with those emotions, my depression lifted, never to return.

Despite the happy ending, I almost missed the connection between my depression and my early parentification because, in my history, other forms of trauma are much more prominent. I was lucky to have a good friend and colleague who helped me see the connection. So this story has one final point: the importance of compassionate support. Perhaps more than anyone, parentified children need a little of the nurture they gave up so long ago.

My Uncle Tim Michna and step father Fan Michna ran this bar at the time those matches were stolen. They were very kind men. Thank you for your stories. Do you haveany old photos?

Thank you for this story. It was very similar to mine when I was 4yrs old. My father worked at the mercury mine and we lived in the town for a short time. My father decided to buy a trailer and move to the mine location. My mother was also depressed and felt isolated. I filled the same roll as you did but with a sister that was less than one year old. My father worked all day and drank all night. I also spent a lot of time at the White Horse Inn. I really enjoyed your story. My story with McDermitt and the White Horse Inn happen between 1962 and 1964. We were not there long and my father was killed in an accident at the mine. We moved back to Idaho 40 miles south of Boise. My mother had years of depression and started drinking. It was a rough childhood but I survived and have had a lot of therapy. Again, thanks for this wonderful story!

Thank you for yours as well! Wow, it sound like we had very similar experiences–and in the same (relatively isolated) corner of the world, too. Congratulations on surviving–and on having the courage to do the hard work of therapy. May the White Horse Inn be a symbol of transformation for us both!

I just found a photo from the ’30’s which I think is The White Horse. My Dad worked around there, with highway crews. I don’t see to be able to paste it into this comment section…