TL;DR

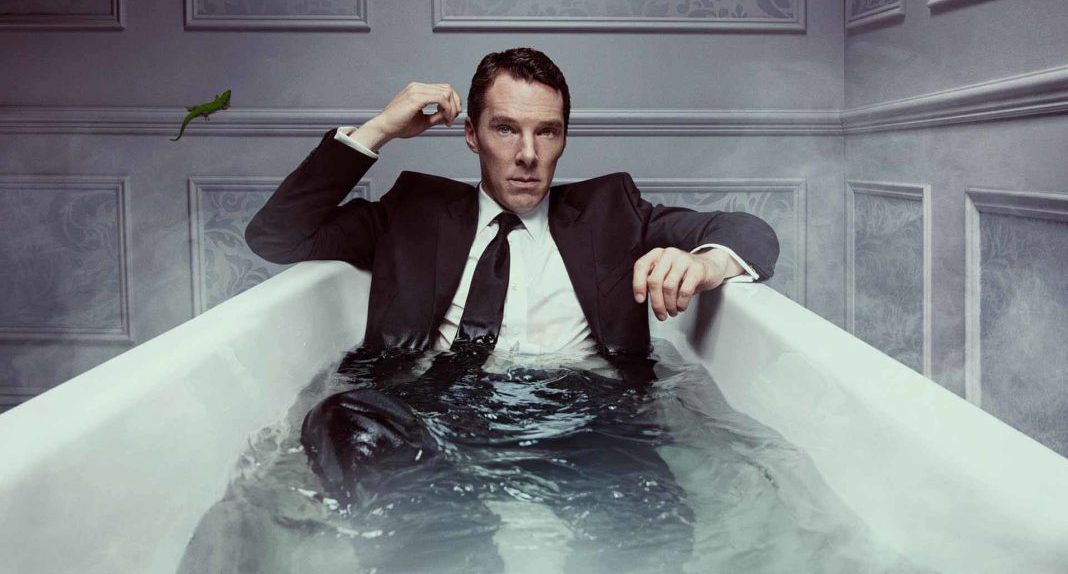

Most of the time, TV treats child abuse in a really simplistic way. It happens, it’s terrible, but the hero cop or doctor or lawyer puts a stop to it, punishes the perpetrator, rescues the child, and we all feel better. TV doesn’t usually plumb the depth of that trauma or explore how it continues to deform the lives of the victims–and the lives of the people around them. PATRICK MELROSE does, and it does so with scorching honesty, wit, and deep (but unsentimental) compassion. Moving back and forth in time, each episode reveals another dimension of this brilliant, damaged man, and it’s in that revelation, not the scenery-chewing at the beginning, that Cumberbatch really shines.

The series might sound grim and earnest, but it’s not. It helps that Patrick is very funny, but the primary momentum comes from the mystery at the heart of the series: what, exactly, did the members of this family do to each other? The writing, acting, and (especially) the directing are so skilled that I really cared about the answer–and about whether Patrick would be trapped by his history or able to wrench at least part of himself free. Possibly the best miniseries of 2018.

EXTENDED CRITIQUE

In depicting childhood abuse and its consequences, television often does as much harm as good. On the upside, it helps raise awareness of abuse, an important first step to developing policies and programs to combat it. On the downside, television does not often handle complexity well. Too often stories about abuse are lurid and simplistic: a monster torments an innocent victim until the hero doctor, cop, or lawyer puts a stop to it and sets things right again. In short, the long, complicated legacy of abuse is not a natural fit for the medium.

An exception, airing right now, is the Showtime mini-series Patrick Melrose. Watching it, I was not at all surprised to learn that the series is based on the autobiographical novels of an abuse survivor, Edward St. Aubyn. The five episodes track a profoundly dysfunctional family back and forward in time, showing how damaged people damage one another. Though a work of art, rather than a case study, it’s as accurate a portrait of a trauma survivor as I have seen on television. Neither lurid nor simplistic, Patrick Melrose might finally show viewers how childhood sexual abuse affects, not just the victims of that abuse, but everyone close to them.

Spoiler Alert: If you want to be surprised by the series, do not read about an episode you have not yet watched, as I will make no effort to obscure plot twists or other revelations.

Episode 1, “Bad News”

If online comments are any indication, many viewers disliked the first episode, seeing Patrick as just another spoiled rich guy behaving badly. Hoovering up drugs and alcohol as he fetches his father’s ashes from New York City, Patrick plays a stereotype based more on Bright Lights, Big City or A Million Little Pieces than on life. I’ll admit, I have mixed feelings about Patrick’s epic drug binge. On the one hand, reckless drug use is a frequent symptom of childhood trauma, so it’s an important part of Patrick’s story. On the other hand, the way it’s portrayed is very unconvincing. One moment, Patrick crawls on the floor, so incapacitated by Quaaludes that he cannot speak or stand; ten minutes later, after a couple lines of cocaine, he becomes Peppy Patrick, spitting out witty staccato quips one after another. It’s a virtuoso performance but not a convincing one.

That’s unfortunate because Benedict Cumberbatch begins the episode with a much more subtle performance. After hearing by phone that his father has died, Patrick leans his head against the wall, closes his eyes, then very slowly opens his eyes and begins to laugh softly. It’s a pitch-perfect performance of an abuse survivor learning that his abuser has died. Relief, even joy, is a normal response to such news, and it’s generally an indicator of severe, sustained trauma. But Patrick is high on heroin, so Cumberbatch renders the joy as though Patrick’s heart is wrapped in cotton wool. Conveying both Patrick’s profound emotional damage and his temporary distance from it, Cumberbatch is brilliant here, as he remains for most of the series.

The episode is visually brilliant, too. From the start, flashes of Patrick’s past constantly intrude on his present. At first, we don’t know what these flashes represent. Some (a man’s hands clenching) seem menacing, some (an open door) seem innocent yet take on menace from the way they constantly intrude on Patrick’s everyday activities. These quick, partial images simulate the brief, intrusive memories that some trauma survivors experience and they offer hints about what happened in the past—just hints, for now, though alert viewers get enough visual information to infer sexual abuse. The series is not coy about its subject matter; rather, it replicates the way traumatic memory works: in disjointed fragments that come when they will and vanish when looked at directly.

Throughout the episode, Patrick’s behavior is classically codependent. He’s both grandiose and self-loathing. He doesn’t know what he wants but becomes angry when he doesn’t get it. He has an instrumental view of other people: their purpose is to realize his transient impulses, and he falls apart when they act independently. Meeting his girlfriend’s pal Marianne, for example, he instantly decides that she will save him from himself and becomes distraught when she declines the job. He is a man with boundaries that are all over the place: from heavily fortified walls to great gaps where boundaries should be. Alternating between imperviousness and toxic vulnerability, Patrick much prefers the former and works hard to maintain his favorite barriers: drugs, bad behavior, aristocratic contempt, and wit.

Girlfriend: Do you think, now that he’s dead, that you could be a little less like him?”

Patrick: Unlikely. I’ll merely have to do the work of two.

Patrick’s wit is often self-aware but in a way that insulates him from the pain of what he’s saying. Despite his initial relief at his father’s death, Patrick is becoming more and more like his father, telling the same terrible stories, using the same slogan (“Only the best or go without”), and abusing the same fatuous people. That he does it all ironically makes no difference, because even his ironic distance is inherited from his father. As so often happens, he’s trapped in a trauma bubble that he can’t escape.

Many scenes resonate powerfully with what we know about the effects of childhood trauma. For example, Patrick experiences terrible conflicts about whether to tell anyone what has happened to him. Part of him yearns to unburden himself, and another part is terrified by the idea. He almost tells his elected savior, Marianne, but, as he murmurs a fragment of his truth, a waiter appears to clear Marianne’s plate, distracting her. The moment gone, he says “Never mind” and immediately tries to seduce her. At other times, he tells his truth indirectly, with sly wit, but literally runs away from the follow-up questions these quips generate. Such ambivalence is a hallmark of childhood abuse, a remnant of the shame that almost invariably accompanies it. To tell feels like revealing the terrible child who deserved the abuse and shared the blame for it, so telling requires enormous courage. In the first episode, we see that Patrick isn’t there yet.

Episode Two, “Never Mind”

The second episode, framed by Patrick’s withdrawal from heroin, takes us back to Patrick’s childhood. On a lavish vineyard estate in the south of France, the family dynamics are as ugly as the landscape is beautiful. Patrick’s father David is a petty tyrant in a silk robe on a tiny balcony. He jokes about controlling his small domain with a machine gun, but he actually controls it with contempt and displays of dominance, such as making a servant stand with a heavy tray of china until her arms quake.

Patrick’s mother, not surprisingly, is completely cowed. Though she’s the one with all the money, she sees herself as trapped, her only option the chemical oblivion of alcohol and pills. Unfortunately, her oblivion extends to her son, whose obvious terror and pain she cannot see, even when he begs her to take him away from his father. Though Patrick vastly prefers his mother’s company, her histrionic self-absorption is as poisonous as her husband’s cruelty. But abused children often try to mentally rescue or rehabilitate one parent, especially if they have no other relatives or siblings to offer emotional support. That is Patrick’s situation, so he lavishes love and attention on his callous mother until she, too, betrays him.

The servant with the shaking arms, Yvette, is Patrick’s only genuine haven, but her affection for the boy angers both parents. They may not want to care for their son, but they damn well won’t let anyone else do it, and, in fact, the sexual abuse starts right after David sees Yvette comforting Patrick from his balcony. In that scene, the images flashed in the first episode link up, forming a fully intelligible narrative. It’s very well done, not lurid and voyeuristic, but also not backing away from the terror of the experience. A great deal of credit belongs to director Edward Berger and to the actors: Hugo Weaving as David Melrose and Sebastian Maltz as young Patrick. There is nothing remotely sexual about the scene; it is the slow, deliberate unfolding of pure terror. Though David claims his cruelty is a gift, offering “the skill of detachment,” all his careful explanation does is delay the inevitable and so amplify Patrick’s fear. In retrospect, we may wonder how David knows that being raped as a child can produce emotional detachment, but, for now, David is purely an instrument of cruelty.

This scene does a real service to victims by keeping the focus on Patrick’s experience and making David’s perspective irrelevant. It achieves this in several ways. One is portraying David piecemeal, rather than as a whole person. We see just his hands clenching on his pajama-clad knees, just his naked ankles from under the bed, just his back with the neatly-made bed behind it. When David and young Patrick are in a shot together, the man is huge and out-of-focus, while the boy is sharp and tiny. While David talks, the camera lingers on Patrick, whose expression is wide open and vulnerable. When it does shift to David, he is backlit, his expression unreadable. We see them together only once, very briefly, as David pushes Patrick toward the bed and closes the door. Backing slowly away from the door, the camera emphasizes that Patrick is now truly alone without hope or help or even a witness.

The director uses similar techniques to emphasize Patrick’s experience in the episode’s final scene, where David again appears out of focus or piecemeal. Blurred in the doorway, he moves forward to become just a giant torso and a huge pair of hands arranging Patrick’s pillow and blanket before delivering the threat that explains why the boy—and the man he will become—have such difficulty talking about the abuse: “If you ever tell your mother or anyone else about today, I will snap you in two.” We do learn a little bit about David, mostly from other people, but the episode does nothing to elicit understanding or sympathy for him, a healthy perspective for Patrick as a young man still suffering the consequences of his father’s abuse.

Episode Three: Some Hope

The focus of this episode is as much social as psychological. From a therapist’s perspective, it’s about Patrick finally revealing what happened to him as a child. The episode begins with a reprise of his father’s warning, “If you ever tell your mother or anyone else about today, I will snap you in two.” Freshly released from a psychiatric hospital where he was treated for alcohol abuse, Patrick keeps himself sober with Prozac and isolation until an old friend of his parents bullies him into attending a lavish party in the country. He attends the party with his old friend Johnny, also in recovery. They rendezvous in London at a meeting of Narcotics Anonymous, where Johnny is a regular.

Patrick dubs NA a cult, though that’s not what we see in the episode. As he waits for the meeting to end, Patrick sits in the back of the room, donning sunglasses and pointing to his watch when the meeting secretary announces “newcomer time.” Walking out, he slams NA’s slogans, jargons, and hypocrisy, but Johnny is unfazed, saying simply, “It’s just a place to confess.” Patrick vehemently insists that such self-revelation is valueless and that he will have none of it. “Don’t try to make me share,” he warns Johnny, adding, “There are things I haven’t told anybody and never will, even you.” He’s a textbook example of someone protesting too much, which underscores how much he wants to tell his story.

That night at the party, he does. His nerves frayed by watching aristocrats’ petty cruelties without drugs and alcohol, he tries to distract himself with sex but quits when he learns that his partner is Johnny’s lover. On an isolated balcony, he tells his friend what happened to him. As with Marianne, a waiter interrupts, but this time Patrick will not be deterred, shouting the startled man into retreat. Johnny, who will later become a psychotherapist, listens carefully and responds with empathy, drawing Patrick out but not pushing.

Patrick describes several details that will be familiar to survivors of abuse. First, his father framed the abuse as punishment without naming the crime. Though Patrick jokes that not knowing “gave it a certain Kafkaesque charm,” the truth is that abusers often take this approach because it builds on children’s natural inclination to believe that what happens to them is their fault. Not knowing what they have done wrong, they conclude that they are bad by nature and don’t have to commit bad acts to deserve punishment. Just existing is enough.

Patrick also describes using a lizard on the wall—a lizard we have seen in flashes throughout the series—as a vehicle to distance himself from the abuse: “I thought if I could somehow put myself inside it, then I might be able to get through this.” This distancing is very common and sometimes results in complete dissociation, where the abuse is recalled as happening to someone else or observed from outside or not remembered at all. Patrick finishes by saying that he’s tired of hating his father and that really living will require him to talk about his painful past. Johnny also recommends making genuine connections with other people, and, that night, Patrick meets the woman who will become his wife.

The title of this episode is apt. By remaining sober, confiding in his friend, and becoming willing to look for love, rather than just sex, Patrick has reason for hope. But it’s only some hope. He has made a start, yet his history is dark and complex, not something easily understood, confronted, or transcended. Patrick may be leaving the drug-addled fury of his youth behind, but he still has a lot of work to do. Fortunately, he has the one thing in the world he most needs to make progress: support.

Episode Four: Mother’s Milk

This episode, more than any other, explores the multi-generational legacy of abuse. Back at the family’s French estate, Patrick is now the angry father and his son Robert the young boy running through the vineyard, listening at doors, and trying to cope with the disturbed adults around him. Patrick’s anger follows his mother’s decision to strip him of the one legacy that he actually wants: the estate. After she informs him of her plans, he begins drinking heavily and ranting about how much he loathes her and fears the legacy she is leaving him.

I loathe the poison dripping down from generation to generation, and I’d rather die than inflict the same thing on our children.

Robert hears it all, and before long we learn that the poison is dripping already, as the boy reveals that he experiences “terrible moments of vertigo, like I don’t exist.”

Patrick’s behavior toward his son echoes both his father’s cruelty and his mother’s oblivion. Drunk and angry when Robert doesn’t want to swim with him, he picks his son up, jumps into the pool with him, and holds the struggling boy underwater. After Robert reveals his “terrible moments of vertigo” Patrick cluelessly replies, “But it doesn’t stop you being a happy child, does it?” Caught up in his own anguish, he rarely appreciates how it affects his family—and, when he does, he’s still unable to change his behavior.

I tried so hard not to pass on the malice and resentment, give them a different sort of childhood. But they’re just fresh mistakes. And Robert notices everything.

Regretful and self-aware as those lines sound, within seconds, Patrick is kissing his houseguest and former lover, starting an affair that will humiliate his wife and help break up his family. Insightful as he can be, supported by a wife and children who love him, he just can’t seem to help himself.

With sex, as with drugs (now mainly alcohol), Patrick alternates between extremes: frustrated deprivation or reckless indulgence. This “road of excess” is typical of survivors who grow up in a chaotic household. With no idea what normal is, they careen between extremes, creating another chaotic household for another generation. If there was “some hope” in the last episode, this one ends with hope dissolving in the drip-drip-drip of inherited poison. Patrick’s wife demands that he change or go, and the episode ends with a long shot of his mother, alone, drinking her 80-proof supper with a straw.

Episode Five: At Last

With his mother now dead, Patrick prepares to speak at her funeral. Unable to draft a speech, he draws a question mark on an index card to indicate that he will speak extemporaneously. Shifting back into the recent past, we see Patrick hit bottom. After demanding to go to Switzerland for an assisted suicide, his mother backs out at the last minute, sending Patrick on a bender that lands him in the hospital with delirium tremens, then in a psychiatric hospital. By the funeral, he is sober again and making his usual caustic quips. “An orphan at last!” he tells his (now) ex-wife. “It’s what I always dreamed of!”

As Patrick gets ready to ad lib his mother’s eulogy, we flash further back, to a surprising conversation not too long after the time of episode three. At the urging of his wife, he tells his mother, “Father used to rape me.” Her response: “Me, too.” Remembering this moment as he begins to speak, Patrick starts sentences he cannot finish and breaks down, overwhelmed. “I can’t do this,” he announces and rushes out of the funeral. Outside, he looses a torrent of rage at his mother that morphs into a torrent of pain. “I thought I was getting better, but I’m such a fucking mess,” he tells his ex-wife. Yet a few hours later, Johnny, now a psychotherapist, puts an entirely different spin on the episode.

Johnny: Well done.

Patrick: For what, a public breakdown?

Johnny: In the trade, it’s what we call a breakthrough.

But Patrick is not yet finished. As the episode closes, he flashes back to a hotel room where he went with his father. From inside the bathroom, he hears his father shouting his name, as he has done so many times. This time, though, young Patrick emerges from the bathroom and says the words that, since the abuse began, Patrick has been burning to say: “It’s wrong. You’re wrong. Nobody should do that to anybody else.” Finally, David Melrose’s face shows emotion: shame, anguish, horror at what he has done.

This is not just a revisionist fantasy, though it is that. It is, more importantly, profound psychic work. The adult Patrick is taking care of Patrick the wounded child, giving him the words that would finally hold his father responsible. It’s a symbolic act of self-empowerment, and it very visibly restores the shame of the abuse to its rightful owner, as we see when David Melrose breaks down at his son’s words. In my Legacy Workshop, we engineer exactly this kind of restoration: imaginatively protecting the wounded child, holding abusers accountable, and returning to them the feelings that are rightfully theirs. We can’t change the past, but we can change our relationship to the past, and this scene offers a powerful glimpse of just how that is done. With his parents’ generation all dead and Patrick on his way back to his family, this small symbolic act offers a good deal more than “some hope.” It offers the prospect of lasting freedom.