Poetry and memoirs convey dimensions of trauma that scientists and clinicians find hard to describe. Below you will find a selection of powerful poems, most from contemporary American writers. The exception is Emily Dickinson, who simply seems modern in her deep understanding of how trauma affects memory. After the poems is a short list of memoirs dealing with childhood trauma. Having done a great deal of autobiographical writing myself, I understand the transformative power of trauma narratives–both for the reader and for the writer. The memoirs I’ve listed are excellent examples.

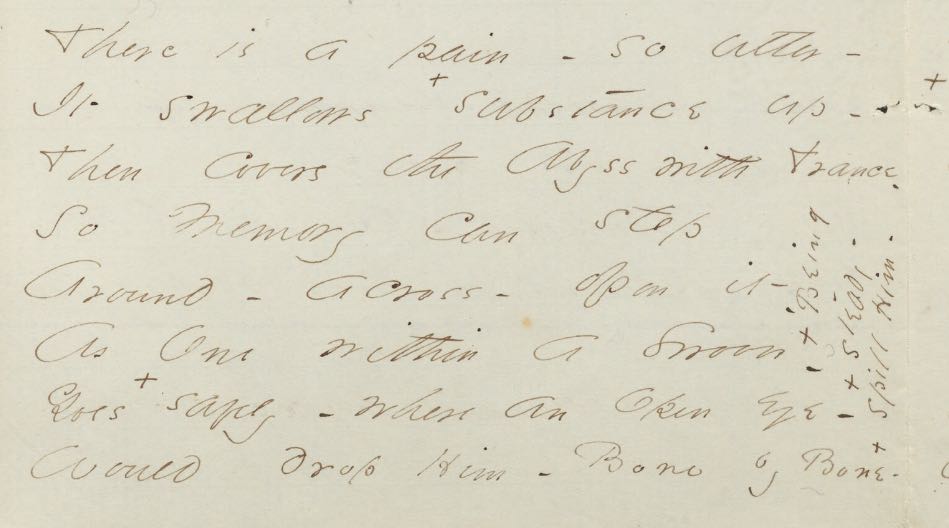

EMILY DICKINSON, “There is a pain — so utter —”

There is a pain — so utter —

It swallows substance up —

Then covers the Abyss with Trance —

So Memory can step

Around — across — upon it —

As One within a Swoon —

Goes safely — where an open eye —

Would drop Him — Bone by Bone —

ROBERT HASS, “The World as Will and Representation”

When I was a child my father every morning—

Some mornings, for a time, when I was ten or so,

My father gave my mother a drug called antabuse.

It makes you sick if you drink alcohol.

They were little yellow pills. He ground them

In a glass, dissolved them in water, handed her

The glass and watched her closely while she drank.

It was the late nineteen-forties, a time,

A social world, in which the men got up

And went to work, leaving the women with the children.

His wink at me was a nineteen-forties wink.

He watched her closely so she couldn’t “pull

A fast one” or “put anything over” on a pair

As shrewd as the two of us. I hear those phrases

In old movies and my mind begins to drift.

The reason he ground the medications fine

Was that the pills could be hidden under the tongue

And spit out later. The reason that this ritual

Occurred so early in the morning—I was told,

And knew it to be true—was that she could,

If she wanted, induce herself to vomit,

So she had to be watched until her system had

Absorbed the drug. Hard to render, in these lines,

The rhythm of the act. He ground two of them

To powder in a glass, filled it with water,

Handed it to her, and watched her drink.

In my memory, he’s wearing a suit, gray,

Herringbone, a white shirt she had ironed.

Some mornings, as in the comics we read

When Dagwood went off early to placate

Mr. Dithers, leaving Blondie with crusts

Of toast and yellow rivulets of egg yolk

To be cleared before she went shopping—

On what the comic called a shopping spree—

With Trixie, the next-door neighbor, my father

Would catch an early bus and leave the task

Of vigilance to me. “Keep an eye on Mama, pardner.”

You know the passage of the Aeneid? The man

Who leaves the burning city with his father

On his shoulders, holding his young son’s hand,

Means to do well among the flaming arras

And the falling columns while the blind prophet,

Arms upraised, howls from the inner chamber,

“Great Troy is fallen. Great Troy is no more.”

Slumped in a bathrobe, penitent and biddable,

My mother at the kitchen table gagged and drank,

Drank and gagged. We get our first moral idea

About the world—about justice and power,

Gender and the order of things—from somewhere.

ROBERT HASS, “My Mother’s Nipples”

We used to laugh, my brother and I in college

about the chocolate cake. Tears in our eyes laughing

In grammar school, whenever she’d start to drink,

she panicked and made amends by baking chocolate cake.

And, of course, when we got home, we’d smell the strong, sweet smell

of the absolute darkness of chocolate,

and be too sick to eat it.

DOROTHY ALLISON, “To the Bone”

That summer I did not go crazy,

spoke instead to my mama who insisted

our people do not go crazy.

We make instead that sudden evening

silence that follows the shotgun blast.

We stand up alone twenty years after

like a scarecrow in a field

pie-eyed, toothless, naming

our enemies and outliving them.

That summer I talked to death

like an old friend, a husky voice

whispering up from my cunt, echoing

around my knees, laughing.

That summer I did not go crazy

but I wore

very close

very close

to the bone.

W. S. MERWIN, “A Garden”

You are a garden into which a bomb once fell and did not explode, during a war that happened before you can remember. It came down at night. It screamed, but there were so many screams. It was heard, but it was forgotten. It buried itself. It was searched for but was given up. So much else had been buried alive.

Other bombs fell near it and exploded. You grew older. It slept among the roots of your trees, which fell around it like nets around a fish that supposedly had long since become extinct. In you the rain fell. In your earth the water found the dark egg with its little wings and inquired, but receiving no answer, made camp beside it as beside the lightless stones. The ants came to decorate it with their tunnels. In time the grubs slept, leaning against it, and hatched out, hard and iridescent, and climbed away. You grew older, learning from the days and nights.

The tines of forks struck at it from above, and probed, in ignorance. You suffered. You suffer. You renew yourself. Friends gather and are made to feel at home. Babies are left, in their carriages, in your quiet shade. Children play on your grass and lovers lie there in the summer evenings. You grow older, with your seasons. You have become a haven. And one day when a child has been playing in you all afternoon, the pressure of a root or the nose of a mouse or the sleepless hunger of rust will be enough, suddenly, to obliterate all these years of peace, leaving in your place nothing but a crater rapidly filling with time. Then in vain will they look for your reason.

RENÉE ASHLEY, “The Shame Fragment”

Harmony, symmetry, the slipping past

or through—and there between clapper

and bell, bottle and lip, the room of no

and every motion: shame with its wet

tongues, its aggravated eye. Shame

wound about your head like tarry air—

the trink and stymie and the damp soul

sweating it out between the skin and

what thrives—in no space at all—inside.

MARY OLIVER, “Love Sorrow”

Love sorrow. She is yours now, and you must

take care of what has been

given. Brush her hair, help her

into her little coat, hold her hand,

especially when crossing the street. For, think,

what if you should lose her? Then you would be

sorrow yourself; her drawn face, her sleeplessness

would be yours. Take care, touch

her forehead that she feel herself not so

utterly alone. And smile, that she does not

altogether forget the world before the lesson.

Have patience in abundance. And do not

ever lie or ever leave her even for a moment

by herself, which is to say, possibly, again,

abandoned. She is strange, mute, difficult,

sometimes unmanageable but, remember, she is a child.

And amazing things can happen. And you may see,

as the two of you go

walking together in the morning light, how

little by little she relaxes; she looks about her;

she begins to grow.

MARK DOTY, “Apparition”

I’m carrying an orange plastic bucket of compost

down from the top of the garden—sweet dark

fibrous rot, promising—when the light changes

as if someone flipped a switch that does

what? Reverses the day. Leaves chorusing, dizzy

and then my mother says

—she’s been gone more than thirty years,

not her voice, the voice of her in me—

You’ve got to forgive me. I’m choke and sputter

in the wild daylight, speechless to that:

maybe I’m really crazy now, but I believe

in the backwards morning I am my mother’s son,

we are at last equally in love

with intoxication, I am unregenerate,

the trees are on fire, fifty-eight years of lost bells.

I drop my basket and stand struck

in the iron-mouth afternoon. She says

I never meant to harm you. Then

the young dog barks, down by the front gate,

he’s probably gotten out, and she says

calmly, clearly, Go take care of your baby.

MARK DOTY, “Underworld”

The new and towering boy in outpatient

folds the lavish scaffold of himself

into a smallish chair as though

it were an ongoing task

to account for all his parts

and he takes us in,

nods his smudge of beard

and smiles privately.

We’ve confirmed his expectations

—no malice or irony in it,

simply a kind of sweetness.

He’s failed to kill himself

last weekend, and has landed

intact, marveling, interested,

his legs (I want to spell long

with two n’s, as Milton spelled

dim with a double m

to intensify the gloom of hell),

craning into one another

then pushing his knees forward

into the speaking circle

where we weigh

ninety minutes

the tonnage of our shame,

the damage yours

only until exactly spoken.

Whose pain’s not a common one?

And then the new man

—all of twenty-two—stretches

his legs entirely forward

and catches my breath

with the name printed across

the tongues of his shoes:

OSIRIS, in bold letters,

maybe a brand too newly stylish

for me to have registered,

but the unlaced word prays

for us to just the right god:

Him torn to pieces,

each bit of His ruin picked up,

each nearly unrecognizable

attended carried and mourned

and is it loved or willed

back into place: the man and boy’s

body radiantly restored.

Or that’s the hope he’s poking

out at us, with his excellent shoes,

while we go on talking until lunchtime.

YUSEF KOMUNYAKAA, “Facing It”

My black face fades,

hiding inside the black granite.

I said I wouldn’t,

dammit: No tears.

I’m stone. I’m flesh.

My clouded reflection eyes me

like a bird of prey, the profile of night

slanted against morning. I turn

this way–the stone lets me go.

I turn that way–I’m inside

the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

again, depending on the light

to make a difference.

I go down the 58,022 names,

half-expecting to find

my own in letters like smoke.

I touch the name Andrew Johnson;

I see the booby trap’s white flash.

Names shimmer on a woman’s blouse

but when she walks away

the names stay on the wall.

Brushstrokes flash, a red bird’s

wings cutting across my stare.

The sky. A plane in the sky.

A white vet’s image floats

closer to me, then his pale eyes

look through mine. I’m a window.

He’s lost his right arm

inside the stone. In the black mirror

a woman’s trying to erase names:

No, she’s brushing a boy’s hair.

ROBYN, AT THE LEGACY WORKSHOP, “Shame”

When I was born

I was a little tiny baby.

My parents fed me gravel.

It scraped down my throat,

Choked me, shut me down.

I opened my eyes wide, searching,

Alarmed—What do I do?

I pushed my throat into the jagged

Rocks, swallowing blood and mucus and stone,

Then breathed a ragged, desperate breath

And wept.

When I was a very young girl,

I had shins and elbows and fingers.

The gravel sat just below where my ribs met.

It melded into one heavy rock which hit-thump

When I ran, pressed out against my lungs,

Making me short of breath.

I coughed blood into the weeds.

Bent over. Kept going.

At home I sat on the edge of the tub in my running shorts

And gulped salt water and mucus and blood.

When I was a teenager,

I had bangs and braces and a trumpet.

One day they said, “What’s wrong with your eyes?”

And blood bloomed across them like fist fights.

What do I do?

“Eat dirt,” said the school principal.

It went down slowly, sticking like

A free and reduced lunch,

And I blew on my trumpet until my eyes,

Ears, nose were red and rocks and

Dirt flew out the horn.

On my eighteenth birthday, I laughed,

And my bones started turning into rock.

My arms ached and screamed and

Turned black.

This black could leach the sweetness

Out of even a lollipop. Or a baby.

Leaving it grey and dull.

This black sags into my space,

Fills my mouth, runs sticky, through my

Toes and punches me in the chest.

I hate the blank, flat, dumbness of it.

MEMOIRS

Allison, Dorothy. (1996). Two or three things I know for sure. London, UK: Penguin.

Castro, Joy. (2006). The truth book: Escaping a childhood of abuse among Jehovah’s Witnesses. New York, NY: Arcade.

Cole, Erin. (2018). The Size of Everything. Santa Barbara, CA: Bella Luna.

Doty, Mark. (2000). Firebird: A memoir. (New York, NY: Harper Perennial).

Ernaux, Annie. (1998). Shame. (T. Leslie, Trans.). New York, NY: Seven Stories.

Fragoso, Margaux. (2011). Tiger, tiger. New York, NY: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux.

Gilmore, Mikal. (1994/1995). Shot in the heart. New York, NY: Anchor Reissue.

Hoffman, Richard. (1995/2005). Half the house: A memoir. New York, NY: Harcourt & New Rivers.

Jeffs, Brent W. (2009). Lost boy. New York, NY: Broadway.

Judd, Ashley. (2011). All that is bitter and sweet: A memoir. New York, NY: Ballantine.

Karr, Mary. (1995/2005). The liar’s club: A memoir. New York, NY: Penguin.

Laird, Chynna. (2011). White elephants: A memoir. Central Point, OR: Eagle Wings.

Pelzer, David. (1993/1995). A child called “it”: one child’s courage to survive. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications.

Scheeres, Julia. (2006). Jesus Land. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint.

Sebold, Alice. (2009). Lucky. New York, NY: Scribner.

Small, David. (2009). Stitches: A memoir. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Walls, Jeanette. (2005). The Glass Castle. New York, NY: Scribner.

Westover, Tara. (2018). Educated. New York, NY: Random House.

Wisechild, Louise. M. (1988/2003). The obsidian mirror: Healing from childhood sexual abuse. Berkeley, CA: Seal.

Wolff, Tobias. (1989). This boy’s life. New York, NY: Atlantic Monthly.